Citizenship Amendment Act: Protests, police, punishment

Atul Krishna | March 24, 2020 | 05:21 PM IST | 6 mins read

NEW DELHI: It was a harrowing two months for India’s university students.

In December, thousands of students from dozens of university campuses rose up in protest against the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019, or CAA, and especially against the police action on students of Jamia Millia Islamia University (JMI) and Aligarh Muslim University (AMU).

But once the states – and in places, university administrations – recovered from the surprise of engineering and management students marching, the crackdown on students followed quickly.

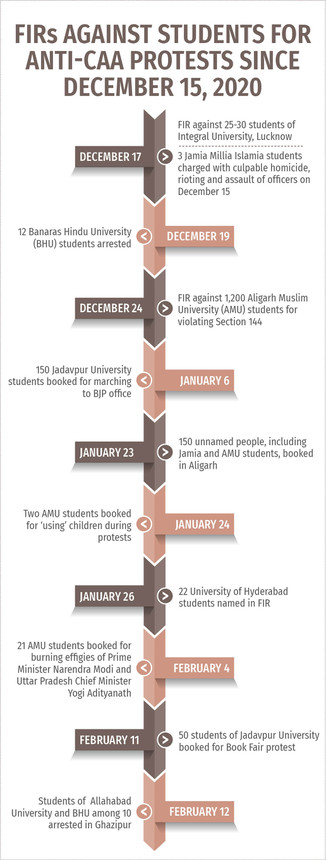

Since December, at least 1,500 students have had police cases filed against them. Thousands have been detained. If not at the hands of the police, students have faced inquiries and gag orders – imposed with varying degrees of seriousness – from their own institutions.

Jamia and AMU

Police action against protesters began on the same Sunday evening, December 15, at Jamia in Delhi and AMU, Aligarh. Jamia students had organised a march to the Parliament against the CAA which made religion a factor in the granting of citizenship and left out Muslims. Outsiders joined in, got violent and three buses were torched. The Delhi Police proceeded to baton-charge and tear-gas students and tear into a library. One student lost his eye.

The university filed a complaint, a student injured that evening has sued for damages. CCTV clips of the violence in the library have been dribbling out online since February 16 stoking further controversy. However, Delhi Police filed cases against seven for culpable homicide (not amounting to murder), including three Jamia students. They later arrested 10 – no student among them.

The same evening Jamia students were left bloodied, the Uttar Pradesh Police baton-charged students in AMU. One lost a hand.

Protests and the police

Police action and surveillance have become familiar to students across cities. On January 6, Left student bodies of Jadavpur University marched to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) headquarters in Kolkata and encountered a pro-CAA rally on the way. Protesting students alleged they had stones thrown at them. Following that, “the police went on rampage-mode and started lathi-charging the students”, said Abinash Dash Choudhury, Jadavpur student and a member of Revolutionary Students’ Front. The next day, around 150 students were booked.

At the International Kolkata Book Fair, on February 8, Jadavpur students raised anti-CAA slogans close to a Vishwa Hindu Parishad book stall where a BJP leader was visiting. Dozens were detained and moved to the police control room. When they raised slogans in front of the control room, they faced batons again. “We were asked to sign an arrest and investigation memo which said that we are surrendering our belongings,” said Srijan Dutta, an undergraduate at Jadavpur. Students said about 50 of them have been booked under charges like assaulting police officers and damaging public property that they vehemently deny.

Hyderabad students face similar charges. On January 26, the police stopped a rally led by University of Hyderabad Students’ Union president, Abhishek Nandan, at the university gate. Students protested at the gate and dispersed by 4 pm. Nandan was among 22 students named in an FIR filed the same day. The charges included wrongful restraint, unlawful assembly, breach of peace, and creating public nuisance. “They (police) told us: If you have come to study then focus on that,” Nandan alleged. “The situation has become such that the government cannot tolerate if someone is raising a question.”

Students in Uttar Pradesh know this only too well. On December 17, over 25 students of Integral University, Lucknow, were booked for organising an anti-CAA march. Two days later, a dozen students of Banaras Hindu University were arrested for organising a rally. They were booked under sections related to rioting. But protests and police cases continued. On February 4, AMU students shouted slogans and burnt effigies of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Home Minister Amit Shah and Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Aditnyanath. Police arrested 21 students for “promoting enmity

between religions”.

Increased surveillance

State police are keeping watch on their activities, complained students. “On the first day (December 19) after the imposition of Section 144 [in Bangalore], three policemen came to the campus early in the morning,” recalled Hamza Tariq, president, Student Bar Association, National Law School of India University. “They asked the students union if they were planning anything. That’s been happening in other colleges too.”

Attempts to deter protests were made elsewhere too. In Ahmedabad, the police withdrew permission for a protest on December 17 at the last minute, “but, by then people had already assembled”, recalled Ashutosh Gudi, student of Ahmedabad University. Around 60 protestors were detained from outside IIM Ahmedabad.

After that, the police visited the IIM campus, said students. The administration allegedly asked students to take their preamble-reading and discussion on CAA and police brutality inside a classroom. “On the day of the event, we found that the police had come to the campus in civil clothes to survey what was happening,” said Anmol Sanchi, a research scholar at IIM Ahmedabad. “They went away once a faculty-member confronted them.” The police, however, denied there was a visit.

Students of Maulana Azad National Urdu University, (MANUU), Hyderabad, alleged they were threatened. “The police called and threatened us,” alleged Umar Faruq, president of the MANUU Students Union. “They said that if we do any such activities, they will file cases against us.” Students also alleged that the administration has shared private details of all hostel residents – such as enrolment numbers and departments – with the police. “We confronted the director about this but he said it was just a routine,” said Faruq. “It isn’t routine. They will start targeting us once we step out of

the university.”

Universities take action

At some institutions, the administrators have imposed restrictions.

On February 18, three research scholars of the University of Hyderabad were rebuked by the administration for organising an anti-CAA protest on January 31. They were also fined Rs. 5,000 each for continuing the sit-in past curfew.

On February 13, IIT Kharagpur revoked permission to a discussion on CAA. Earlier, the North East Cell of Shri Ram College of Commerce, Delhi University, was compelled to cancel its event on the CAA on January 23. “We were told that they received information about the possibility of violence on campus if the event was to take place. We were also told that there was no balance in our panel and all our speakers had the ‘same bent of mind’,” they said in a statement.

Efforts to control students’ social media use have intensified. On January 28, IIT Bombay instructed students “not to practice anti-national activities”. A 15-point code mailed to them prohibited the distribution of posters or pamphlets without permission. IIT Delhi pushed its Board for Student Publications to pull down its report on the December 16 march on campus. On December 19, the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, issued a statement saying it was prohibiting “activity in the nature of the strike, dharna or demonstration or gherao in and

around AIIMS”.

On other campuses, the consequences were harsher still. In December, a student of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti Urdu, Arabi-Farsi University in Lucknow was rusticated for posting the announcement for an anti-CAA protest on social media. On January 1, IIT Kanpur instituted an inquiry into a protest gathering on December 17. The complaint was mainly against the reading of Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s classic poem, ‘Hum Dekhenge’ at the protest. The IIT Kanpur administration told the press it would examine whether the poem is “anti-Hindu”.

Write to us at news@careers360.com.

Follow us for the latest education news on colleges and universities, admission, courses, exams, research, education policies, study abroad and more..

To get in touch, write to us at news@careers360.com.