‘Creamy layer’ rule will make Dalit, Adivasi teachers more scarce; deal a blow to diversity: Manoj Mitta

Atul Krishna | August 7, 2024 | 12:03 PM IST | 6 mins read

The advisory on ‘creamy layer’ is non-binding but as this has come from the Supreme Court, it could encourage some states to extend the creamy layer filter to SC, ST quotas too.

NEW DELHI: In a majority verdict on August 1, a seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court allowed states to sub-classify Scheduled Castes (SC) by overturning a two-decade-old ruling. The bench also made several notable comments on introducing “creamy layer” to SC and Scheduled Tribes (ST), much like the existing system for the Other Backward Classes (OBC). In OBCs, the “creamy layer” – those with family income over Rs 8 lakh per year – is not eligible for reservation.

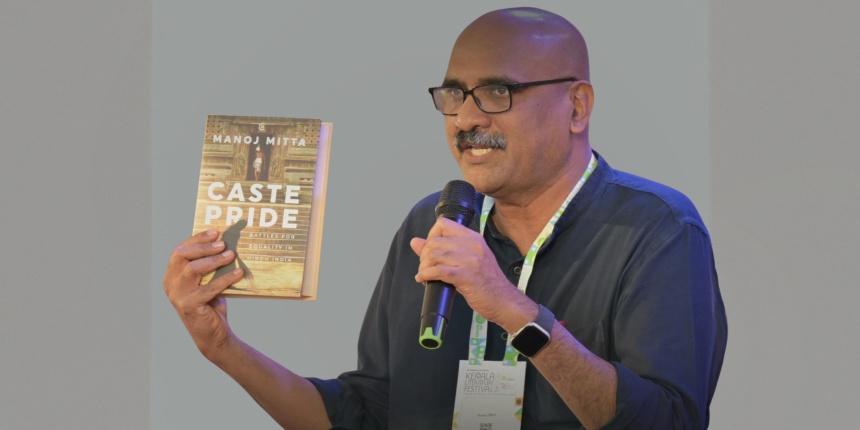

Manoj Mitta, author of the award-winning book, Caste Pride: Battles for Equality in Hindu India, speaks to Careers360 on the judgment and its impact on reservation. Edited excerpts below.

What do you think of the judgment and how does it impact reservation?

There are two broad aspects to the verdict by a seven-judge bench. The main aspect is that by a 6-1 majority, it overrules a 20-year-old ruling of a five-judge bench that forbade states to sub-classify Scheduled Castes.

The law laid down by the August 1 judgment as embodied in the opinion of Chief Justice D Y Chandrachud is an enabling one. It allows states the discretion to sub-classify SCs as in the case of OBCs to help the more needy and deserving castes access quotas. This is a landmark decision as it gives judicial recognition to the reality of “inter se backwardness” among SCs. In other words, even among the castes that historically suffered from the stigma of untouchability, some are more backward than others in keeping with BR Ambedkar’s famous formulation of “graded inequality” throughout the caste hierarchy.

The other broad aspect of the judgment backed by four judges is more controversial. It’s about applying the creamy layer criterion, introduced by the Supreme Court for OBC reservations in 1992, to SCs and STs as well.

This opinion, expressed mainly by Justice BR Gavai, is more controversial because no such question about creamy layer was discussed before the seven-judge bench. So, without giving any opportunity to the parties before the court to state their views on this aspect (STs were not even represented before it), Gavai came up with the drastic conclusion of weeding out from the ambit of affirmative action all such members of the beneficiary groups who were no longer backward on account of the wealth or positions enjoyed by them.

While the sub-classification principle gives preferential treatment to castes as such, the creamy layer principle operates at the individual level. Though both are conceptually designed for effective targeting of the reservation scheme, empirical data shows that the creamy layer principle has already proved to be counterproductive among OBCs. There have been many instances of OBC quotas remaining unfilled as the creamy layer principle drastically reduces the pool of eligible candidates. This is perhaps why Gavai clarified that the criteria for the exclusion of the creamy layer from the SCs and STs could be different from those of the OBCs.

What part of the judgment is enforceable?

As I said, the law laid down by the judgment is only an enabling one; it’s not mandatory. The judgment does not force any government, whether state or central, to sub-classify SCs for better targeting of reservations. States like Andhra Pradesh and Punjab that have already passed laws in this regard or those that propose to do so can now proceed with such sub-classification.

Since the issue of creamy layer is outside the ambit of the case, the exertions of Gavai and the three judges who concurred with him constitute obiter dicta, the non-binding part of the judgment. But then, as this advisory has come from the highest court of the land, it could well encourage some states to extend the creamy layer filter to SCs and STs too.

Also read IIT Bombay: 90% undergraduate students to opt for early exit were SC, ST, OBC

Has the court clarified on how the sub-classification will be determined?

Yes, whether the sub classification is done for the SC quotas in government jobs or educational institutions, the judgment authored by Chandrachud says that it should be determined on the basis of the condition prescribed by Article 16(4) of the Constitution for government jobs. It is that any kind of provision can be made for a backward class of citizens that is not adequately represented in government services. Accordingly, Chandrachud suggested that sub classification should be based on “inadequate representation” of the castes concerned within the SC fold.

So, if any state exercises the option of sub-classification, it will have to collect data on the inadequacy of representation in government services as an indicator of backwardness.

How do you think the sub-classification should be determined?

The intended purpose of sub-classification, namely, to target the most backward of the backward classes of citizens, is clearly consistent with the social justice objective of the Constitution. But as it does not make any express provision for such fine-tuning, Chandrachud filled the gap by applying the Article 16(4) condition to sub-classification. And although Article 16(4) is only for government jobs, he extended its condition to educational institutions as a measure of inter se backwardness. This bit of creative interpretation could well be cited as one of the grounds for reviewing the judgment.

The judgment has already brought out fissures within the Dalit camp on sub-classification. If Mayawati and Chirag Paswan have come out against it, they seem to be clearly driven by the interests of the relatively dominant castes in the SC category (Jatavs in Uttar Pradesh and Dusadhs in Bihar).

Also read NEET: How NRI quota dilutes ‘merit’ but faces none of the flak reservation gets

What do you think of the comments on “creamy layer”? Will the judgment make it possible to exclude the “creamy layer” from reservation?

It is interesting that Justices BR Gavai and Pankaj Mithal, two of the judges batting for the exclusion of the creamy layer of Dalits and Adivasis, come from entirely different spaces. While Gavai is a Dalit and an avowed Ambedkarite, Mithal calls for a “fresh re-look” at the very policy of reservation and “evolvement of other methods” for uplifting the depressed communities. In fact, Mithal digressed to the extent of claiming that the varna system sanctioned by Hindu scriptures was “misconstrued” as the caste system which alone was found to be “socially non-acceptable”.

This gratuitous distinction, if anything, reflects the bias of upper castes or rather the creamy layer of Hindu society.

IIMs, IITs, and other central universities are not filling SC, ST teaching posts even with the current system. What impact would the introduction of a “creamy layer” have under such circumstances?

The revival of the sub-classification option after a lapse of 20 years is fraught with political challenges. It is therefore unlikely that the Narendra Modi Government will be in any hurry to take up another sensitive issue like creamy layer. The existing deficits in filling SC and ST quotas in central educational institutions is due to the susceptibility of academics to the deeply entrenched caste prejudice in society at large. If and when the creamy layer rule is introduced in IITs, IIMs and other central universities, Dalit and Adivasi teachers are likely to become even more scarce. It will deal a blow to diversity in the name of social justice.

What are your thoughts on some of the comments made by the judges, such as how the second generation should not be eligible for reservation?

You are actually paraphrasing Justice Mithal. His exact words were: “If any generation in the family has taken advantage of the reservation and has achieved higher status, the benefit of reservation would not be logically available to the second generation.” Does this mean that if an impoverished Dalit achieves higher status by getting the job of a peon or a clerk in a government office, his daughter should be denied the benefit of reservation when she sits for the highly competitive civil services examination?

Follow us for the latest education news on colleges and universities, admission, courses, exams, research, education policies, study abroad and more..

To get in touch, write to us at news@careers360.com.

Next Story

]Through CUET, NTA is disrupting the academic cycle of JNU and every other university: JNUSU president

Lakhs of students suffer every year because of NTA’s incompetencies, but there is no accountability, said JNUSU president Dhananjay as he shares his views on NTA, CUET, casteism and fund cuts in universities.

Sanjay