Unequal Online: Poor children are disadvantaged even on the internet

Team Careers360 | February 15, 2020 | 09:09 AM IST | 4 mins read

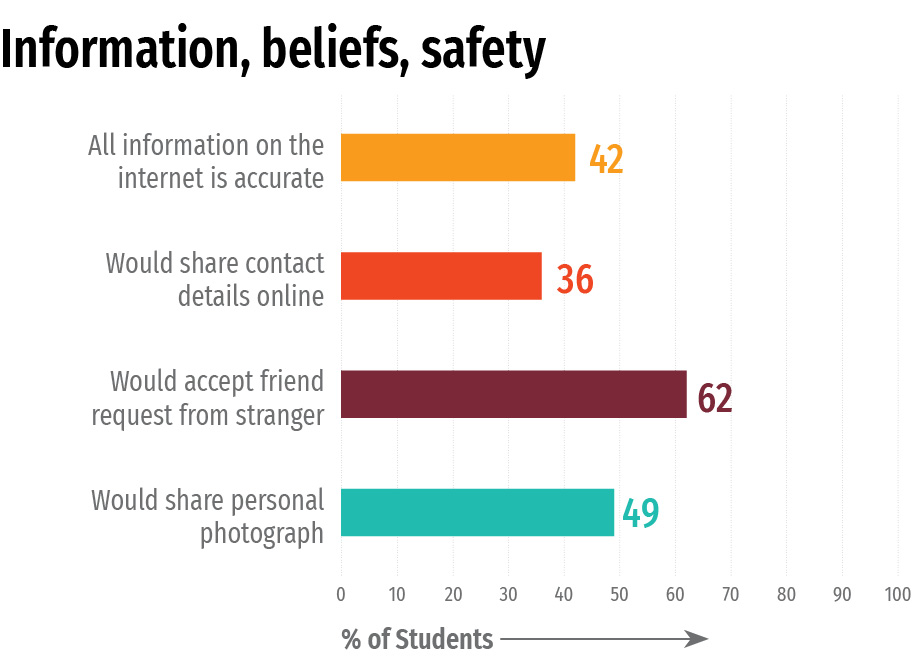

NEW DELHI: More than 40 percent of over thousand students surveyed for a study said they believe all they read online. More than a quarter would share their contact details with strangers; over 60 percent would accept a stranger’s friend-request on social media and nearly half would share their photographs.

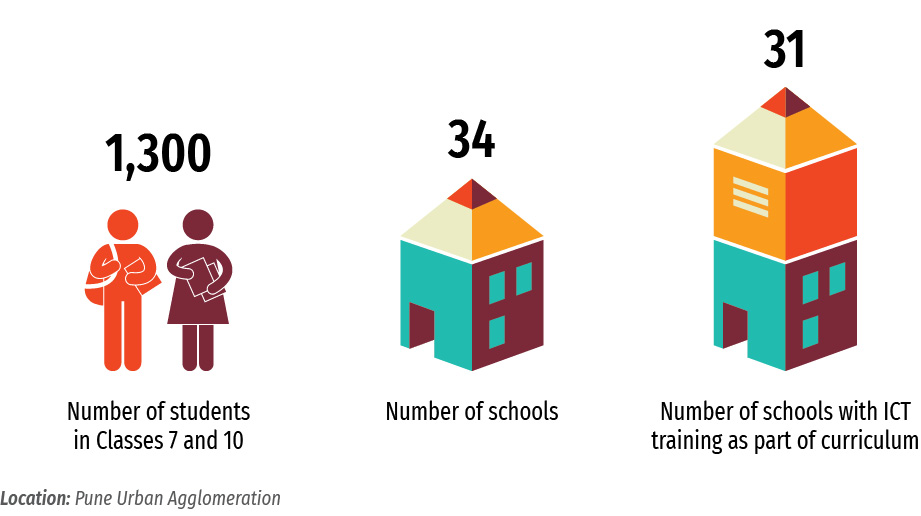

Researchers at the Centre for Communication and Development Studies in Pune studied the use of information and communication technology (ICT) among 1,300 school children from Classes 7 and 10 in Pune. Released in December 2019, their report, Catching up: Children in the margins of Digital India, “challenges the over-optimistic view of children as ‘digital natives’ and of ICTs as empowering all children equally”. The report is a reality-check for policymakers who increasingly take ICT-skills for granted. The survey was conducted in the Pune Urban Agglomeration which, as the report says, is “one of the fastest-growing urban areas in India, an IT hub and one of India’s ‘Smart Cities’”.

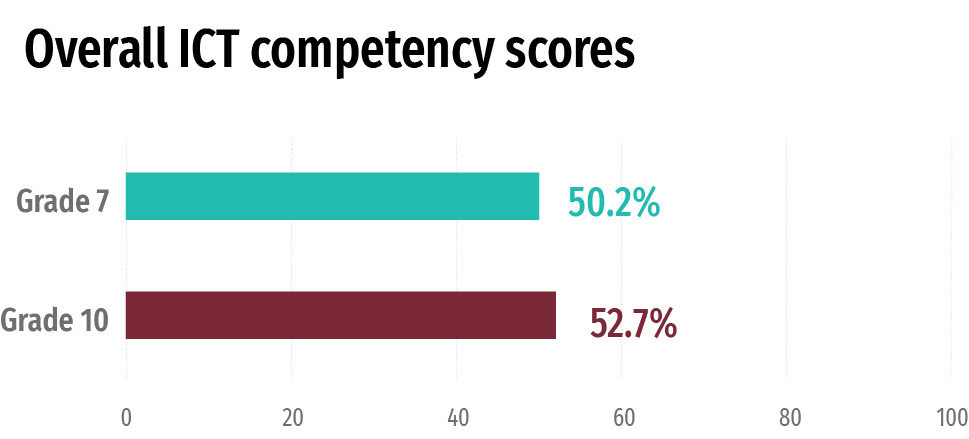

To study the degree of ease and safety with which children negotiate the internet, the study’s authors took an ICT “competency quiz” that covered four areas – “operating computers”, “managing information using basic computer programs”, “communicating information” and “using and evaluating online resources”. The study also looks at ICT use across socioeconomic segments and “points to the vastly unequal digital starting point for young urban citizens... already held back by poverty and social exclusion”. Scholars from Azim Premji University wrote the companion Technology in Education: The Gap between Policy and Praxis.

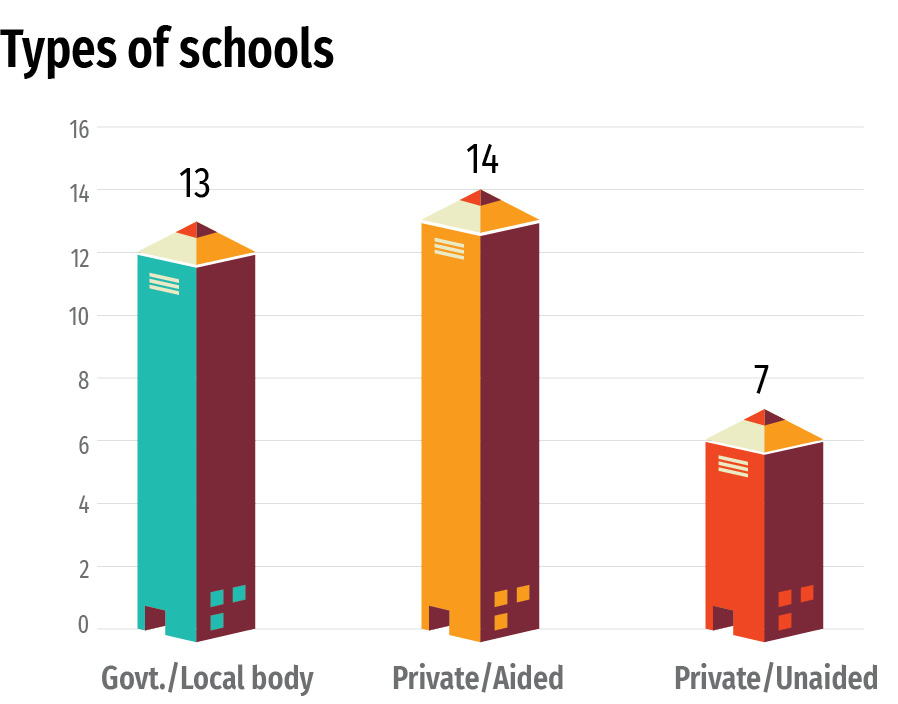

Thirty of the 34 schools were either government schools or low-fee private ones with large proportions of children from economically and socially disadvantaged backgrounds.

Unequal access

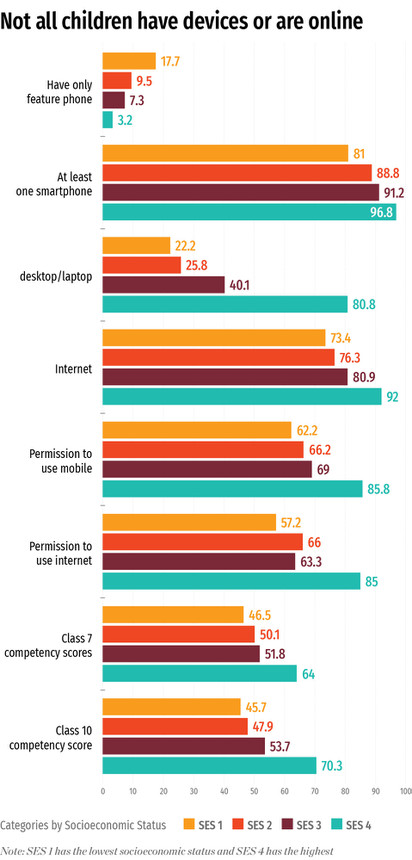

Of the students, 88 percent had access to smartphones but just 35 percent to computers.

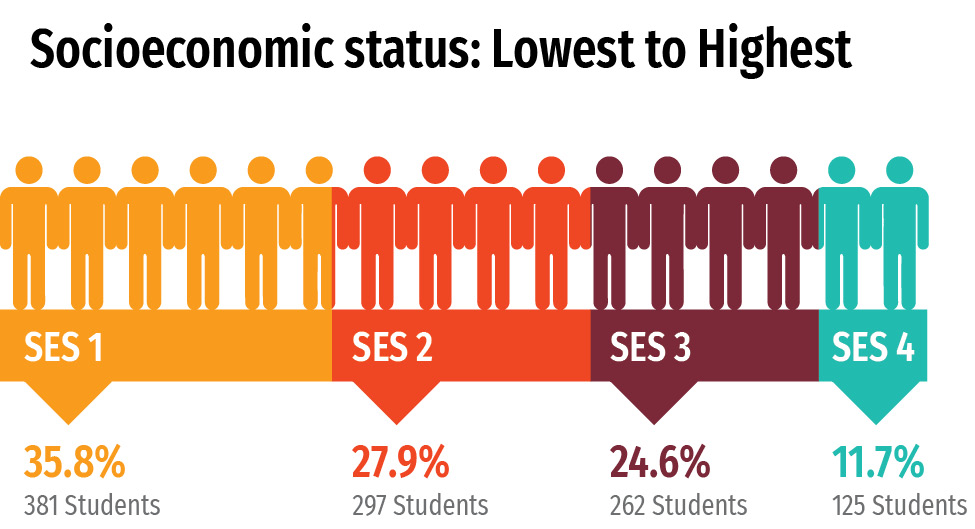

Contrary to the popular belief that all youths are now online, a quarter of the children in the poorest segment included in the study (SES 1 with 381 children) said “they did not know how to operate computers or the internet at all”. Ownership of a family desktop or laptop is naturally contingent on income. Less than a third of the children in SES 1 and 2 had either at home whereas over 80 percent of those in SES 4 did.

The the gap in family ownership of smartphones was found to be narrower but the report notes that “a significant 19 percent of students from SES 1 came from households that did not have the economic capital to buy even an entry-level smartphone”. Also, a family’s possessing a smartphone does not imply the student has permission to use it – some get access for only brief periods and in secret.

Similarly, different schools offered different levels of exposure to ICT. Three schools – all government-run – did not offer any ICT programme at all.

This inequality is reflected in the scores of the four groups. Nearly a quarter of the students in the poorest segment didn’t know how to operate computers or the internet.

Unequal skill and experience

The unequal access also translates into differences in the way the internet is used and experienced.

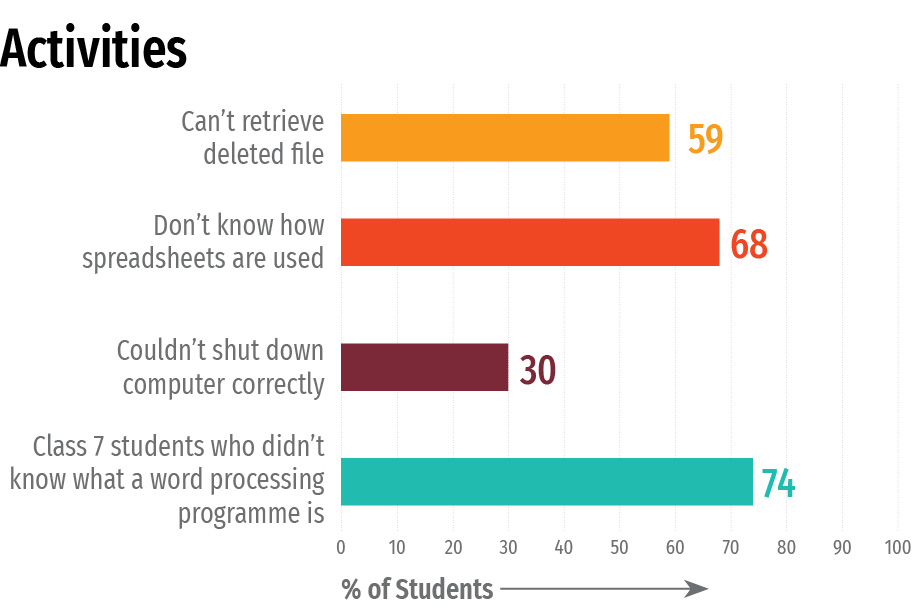

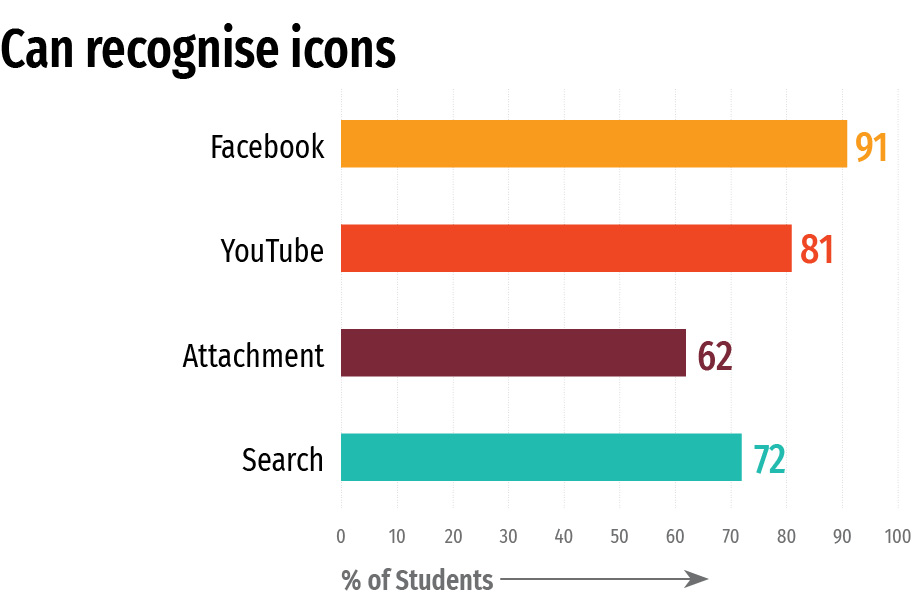

While most students seemed capable of using the internet for social-networking and entertainment, they couldn’t use it for other benefits __ 91 percent identified the icon for Facebook, but only 62 percent could identify the symbol for email attachment. Over 80 percent knew the icon for YouTube but 59 percent couldn’t retrieve a deleted file. Over a quarter couldn’t shut down a computer correctly.

“The skills that children acquire informally on devices such as smartphones may suffice for entertainment and simple searches but not for lifelong learning, discerning use of digital information and media, or livelihoods,” says the study.

While ICT programmes in schools are expected to mitigate the effect of unequal access at home, the study has found that such training is “not by itself able to counteract the home effect – the pervasive influence of economic, social and cultural capital on the ICT awareness and capability of children.” The “access divide” it says, “is only the first level of digital inequality”. The children also face other barriers such as language and lack the wherewithal to deal with situations like cyber-bullying.

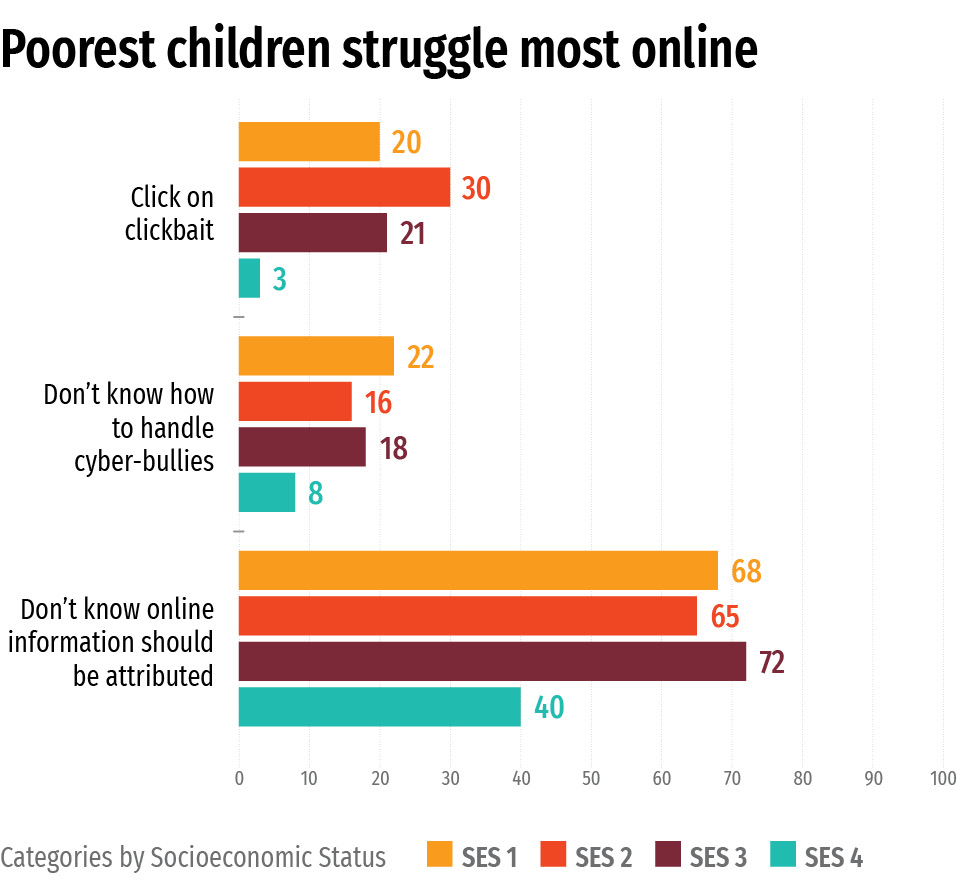

The poorest children are also the least careful online and most prey to disinformation, the study has found. The top income group (SES 4) is most skeptical about what it reads online while the majority of the children from the poorest category (SES 1) didn’t know that even information shared online must be attributed to sources.

The skills that children acquire informally on devices such as smartphones may suffice for entertainment and simple searches but not for lifelong learning, discerning use of digital information and media, or livelihoods

All graphics by Shvetank Verma

Write to us at news@careers360.com.

Follow us for the latest education news on colleges and universities, admission, courses, exams, research, education policies, study abroad and more..

To get in touch, write to us at news@careers360.com.