How the turmoil over college fees has been a decade in the making

Abhay Anand | February 5, 2020 | 12:59 PM IST | 8 mins read

NEW DELHI: Shashank Kumar is in the final year of BA History at Delhi University (DU). From the economically backward Dumka district in Jharkhand, Kumar has been counting on subsidised public education. Upon graduation, he planned to study International Relations in Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and then try for the civil services. But the possibility of a fee increase in JNU has cast a shadow over his dream.

Kumar’s father earns Rs. 10,000 per month at a garments shop. Despite having two more school-going children at home, he sends Rs. 2,500 of that to Kumar to cover the cost of studying and living in Delhi. “After Class 12, my father decided I should take admission in DU as options in Jharkhand and Bihar are limited.”

The first year, Kumar lived with relatives in Uttam Nagar, saving on the cost of accommodation. But he subsequently moved to a colony close to his college and JNU. To supplement money his father sends, Kumar privately tutors children. He had hoped that with JNU’s subsidised housing, low fee and scholarships, he could stop taking his father’s money.

But in late September, the university decided to increase its hostel charges dramatically. Even after intense protests, there hasn’t been a complete rollback. Fees at other premier institutions, including the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and film and media training institutions, have increased as well. Widespread protests have compelled some to rollback or rethink, but students worry the relief is temporary. The plans of thousands like Kumar stand jeopardised. But as educationists and former university administrators say, the fee crisis has been gestating for years.

A decade of hikes

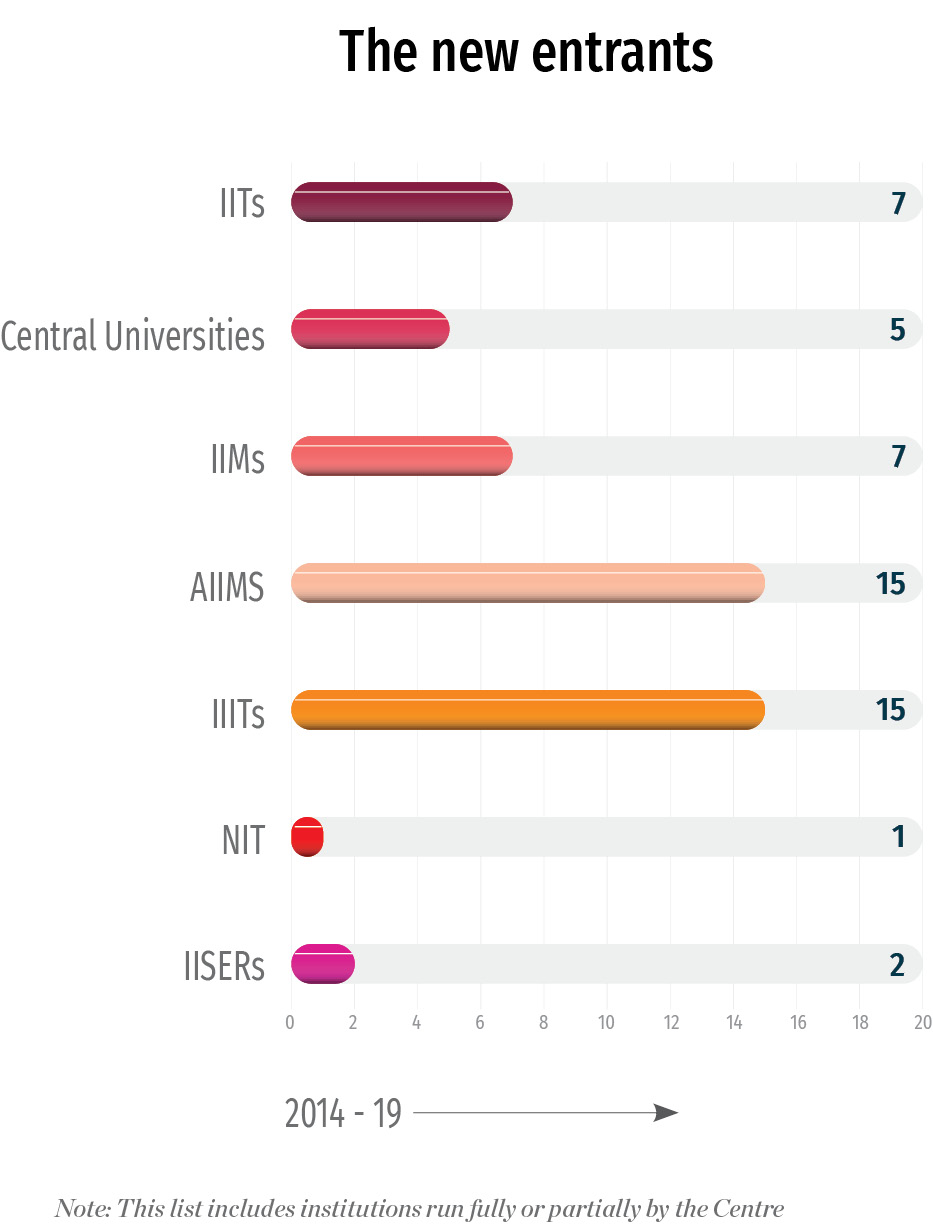

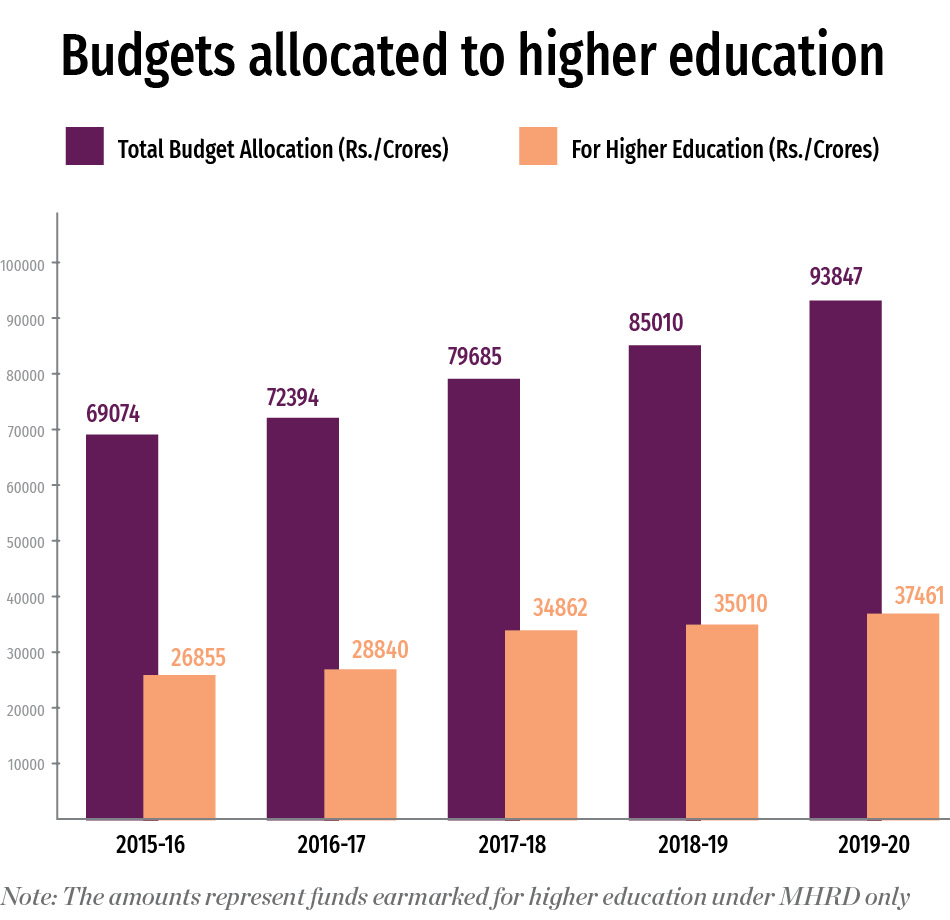

.jpg) The first glimmerings were seen about a decade ago.Education is on the concurrent list of subjects in India, funded and regulated jointly by the states and the Centre. The perennially under-resourced state universities felt the funds-crunch first and struggled to pay even salaries. Central institutions were better off, but even they struggled under a range of pressures – the increasing cost of operation, expansion with new centres and programmes, and a dramatic growth in student strength after the introduction of the 27 percent quota for the Other Backward Classes in 2007. With the 10 percent economically backward section (EWS) quota for the upper-caste poor, there was a further increase in seats.Meanwhile, in 2009, the Right to Education Act was passed to make elementary education – Classes 1 to 8 – free and compulsory and Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, the main scheme supporting the law, began to draw the bulk of the education funds. It continues to do so. Funding for higher education started falling short of what was required and the Union Government started nudging centrally-run institutions to start devising ways of generating funds on their own. One way to do that was by hiking fees.

The first glimmerings were seen about a decade ago.Education is on the concurrent list of subjects in India, funded and regulated jointly by the states and the Centre. The perennially under-resourced state universities felt the funds-crunch first and struggled to pay even salaries. Central institutions were better off, but even they struggled under a range of pressures – the increasing cost of operation, expansion with new centres and programmes, and a dramatic growth in student strength after the introduction of the 27 percent quota for the Other Backward Classes in 2007. With the 10 percent economically backward section (EWS) quota for the upper-caste poor, there was a further increase in seats.Meanwhile, in 2009, the Right to Education Act was passed to make elementary education – Classes 1 to 8 – free and compulsory and Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, the main scheme supporting the law, began to draw the bulk of the education funds. It continues to do so. Funding for higher education started falling short of what was required and the Union Government started nudging centrally-run institutions to start devising ways of generating funds on their own. One way to do that was by hiking fees.

In 2011, the Anil Kakodkar Committee suggested increasing the fees at the IITs to over Rs. 2 lakh per year “considering the high demand for IIT graduates and the salary that an IIT B.Tech is expected to get”. The IITs and National Institutes of Technology (NITs) first raised their fees from Rs. 50,000 to Rs. 90,000 per year in 2013 and then the IITs hiked it further to Rs. 2 lakh just three years later. Also in 2013, the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) advised central universities to increase fees to cut down their dependence on the government, “which helps them with grants”.

Other institutions started increasing their fees as well. These included the Indian institutes of Science Education and Research (IISERs), Panjab University and Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University

in Delhi.

Fees and cost

Judging by the fee-structures of central and state universities, undergraduate students in a public institution pay approximately Rs. 5,000-6,000 per year for a non-technical course. Income from tuition fees is not enough to cover the salaries of teaching and non-teaching staff, development and maintenance of infrastructure, the costs of running libraries, laboratories and other activities. The gaps were closed with government grants.

“The government needs to make broader policies related to the funding of universities,” Sopory continued. “How will they fund for the next 20 years? The universities and the government need to plan the expansion together and decide how much money the government is willing to commit and what methods universities must adopt to generate funding.”

Apart from the increase in numbers due to reservations, the 2000s also saw expansion of higher education with a large number of centrally-run institutions, including several central universities, IITs and IIMs, being announced and opened. The budget did not increase sufficiently, say experts. “The government no longer wants to put money in education,” said former University Grants Commission chairman, Sukhadeo Thorat. “It is not that the government does not have money. It is a matter of policy, which means they want to promote the private and neglect the public.”

“The government no longer wants to put money in education,” said former University Grants Commission chairman, Sukhadeo Thorat. “It is not that the government does not have money. It is a matter of policy, which means they want to promote the private and neglect the public.”

No long-term planning

Institutions are adopting different strategies to cut costs and the most highly-regarded ones are also under the most pressure to leverage their ‘brand’ for revenue.

In JNU, the hostel and mess fees were hiked and new service and utility charges imposed. Panjab University, placed in the top 200 in global rankings, has been struggling for years. In 2017, it increased the tuition fee, causing huge unrest among students with 66 of them being charged with sedition. A massive fee hike is reportedly in the offing for the All India Institute of Medical Sciences as well.

Institutions like Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) and Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute (SRFTI), not under the purview of the MHRD, increased the fee for the entrance test to Rs. 10,000 – more than most private institutions. A hunger strike by students forced a rollback, but the tuition fee has also nearly doubled over the past few years.

Rohan Patil, an engineering student in Pune who hopes to join FTII said: “The recent hike in [exam] fee definitely affects the examination. Even if people have the skill to crack it, many are unable to afford the fee. Examination fees must be kept low. Now that it has been reduced, we can expect more students to register.”

The Centre has offered no practicable roadmap on how institutions that have relied on public funds for decades may be weaned off without affecting the access of disadvantaged students to quality education. There must be a “thought process” before a hike, said Sopory. “How much fees must be increased, if it is required, will the fee be raised annually or every 10 years – I don’t think much thought is given to this.” If a hike is necessary, a committee should be formed for all central universities, added Thorat.

The absence of long-term planning results in sudden increases that directly impact students, are highly unpopular and yet, make little difference to the larger problem of shrinking resources. “During my tenure as the VC [of JNU], we calculated – the same way it has been done now – what would happen if we increased the fee by Rs. 300,” said Sopory. “We realised we would become inaccessible to students from economically weaker backgrounds but the university would still not be able to generate more than Rs. 2-3 crore. Is this amount too much of a burden on the government?” Even the fee-hikes in technical programmes are not always explained convincingly. Raghunath K. Shevgaonkar, former director of IIT Delhi, believes the increase for the IITs’ undergraduate programmes was “to some extent justified” – although there were protests – but not the proposed increase for the M.Tech programme. In September, the IIT Council which governs the institutions proposed a 10-fold hike in fees to deter students who are simply waiting for jobs.“If a student has to pay a heavy fee for M.Tech without any scholarship, they will simply withdraw,” said Shevgaonkar. “This will have a long-term impact on research output. If you look at the IITs, their UG students go abroad after B.Tech. It was the M.Tech students who were serving the nation by working in various PSUs or research labs. Even if some students left the course in between to join some job, that does not mean the entire programme must be killed.”

Even the fee-hikes in technical programmes are not always explained convincingly. Raghunath K. Shevgaonkar, former director of IIT Delhi, believes the increase for the IITs’ undergraduate programmes was “to some extent justified” – although there were protests – but not the proposed increase for the M.Tech programme. In September, the IIT Council which governs the institutions proposed a 10-fold hike in fees to deter students who are simply waiting for jobs.“If a student has to pay a heavy fee for M.Tech without any scholarship, they will simply withdraw,” said Shevgaonkar. “This will have a long-term impact on research output. If you look at the IITs, their UG students go abroad after B.Tech. It was the M.Tech students who were serving the nation by working in various PSUs or research labs. Even if some students left the course in between to join some job, that does not mean the entire programme must be killed.”

Generating funds

In 2017, the Centre made its most radical effort yet to restructure higher education finance. It established the Higher Education Finance Agency (HEFA) to extend infrastructure loans to higher educational institutions by mobilizing funds from the market. This aimed to replace the capital grants to IITs and central universities with loans. The interest on the loans would be paid through the Centre’s budget but institutions were expected to pay the principal amounts from their “internal accruals” made through research and consultancy. As their annual reports show, at the time, no IIT – let alone general universities – generated enough revenues to repay the amounts they had to borrow.

The HEFA is directly responsible for much of the anxiety over funds. Institutions have launched endowment funds, hoping to attract donations. IIT Delhi has received an initial commitment of Rs. 250 crore but the universities are less likely to receive such generous support.

Thorat said: “I do not think any public university can generate its own funding, some of the faculty members generate their funding through research projects. In foreign countries public institutions get full funding, then they also generate some money through endowment or research projects.”

Survey: How expensive is your college education for you?

Follow us for the latest education news on colleges and universities, admission, courses, exams, research, education policies, study abroad and more..

To get in touch, write to us at news@careers360.com.