Mega Universities: How do you run a university with over 600 colleges?

Abhay Anand | March 25, 2020 | 09:34 AM IST | 8 mins read

NEW DELHI: Every year, it is a challenge to conduct examinations in Sawantwadi, in the Konkan region of Maharashtra. Three colleges of this Konkan town are affiliated to Mumbai University, almost 650 kilometres away. Going to the university for any work is a big challenge. Administering the colleges in this region is an equally big one for Mumbai University. The Konkan people have long demanded a separate university for their area. This problem is not unique to Maharashtra either.

The University of Mumbai, like most universities in the country, has a federal structure. The central administration and its postgraduate departments form the core that sets standards for and regulates a number of affiliated institutions, typically colleges, for undergraduate studies. These colleges can be fully public, aided or private.

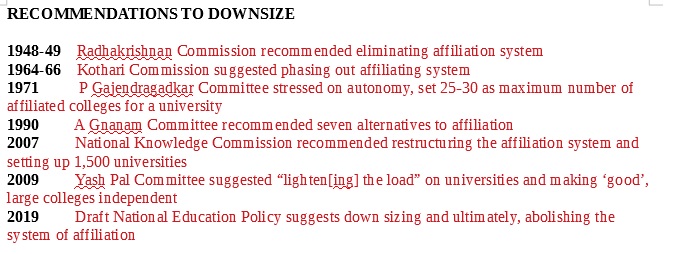

The draft National Education 2019 is only the latest policy roadmap to recommend abolishing this system of affiliated colleges. Education commissions have regarded this structure with concern for years and it’s easy to see why. Some state-run universities are so bloated, their central cores, instead of focusing on research and innovation, have been reduced to just conducting exams and managing welfare schemes and promotions.

India’s five biggest universities regulate a staggering 4,209 colleges and centres between them, enrolling lakhs of students. The largest, Chhatrapati Shahu Ji Maharaj (CSJM) University, Kanpur, alone has close to 1,000 affiliated colleges spread across 14 districts of Uttar Pradesh. Mumbai University, with over 800 affiliated colleges enrolling 8.5 lakh students conducts 8,500 examinations in a year. Savitribai Phule Pune University, Maharashtra, and Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University, Agra, Uttar Pradesh are about the same size as Mumbai University.

The story behind their bulk is the same one behind most of public higher education – underfunding, teacher-shortage, and systems whose growth simply hasn’t kept pace with the growth in the number of students.

On downsizing

The Draft NEP suggests that all affiliated colleges develop into autonomous degree-granting institutions or universities by 2032, or merge completely with the universities they are affiliated to. But as the administrators of the largest of these giants remind, this is easier said than done. If successive recommendations to downsize have been ignored, it’s because the splitting of universities into manageable sizes will require far greater financial support from government.

“I appreciate the idea of downsizing big affiliating universities and of course they will function better,” said Neelima Gupta, Vice-Chancellor, CSJM. “But it is necessary to look into the practical issues. We will require more infrastructure, more faculty of which there is a scarcity. Fewer students would mean lesser income for the university. Small universities can only function better if the government provides full grants.”

The affiliation system was working fine till about the 1970s. As the number of colleges started rising with the student population, the administrative burden on the affiliating universities swelled.

The affiliation system was working fine till about the 1970s. As the number of colleges started rising with the student population, the administrative burden on the affiliating universities swelled.

In 1971, Gajendragadkar Committee suggested that a university should have no more than 25-30 affiliated colleges. If the number grows further, another university must be established to handle the new colleges.

Maintaining quality

The biggest challenge for administrators of mammoth institutions is maintaining quality standards across colleges, said S. Ramachandran, former Vice-Chancellor of Osmania University, Hyderabad.

Suhas Pednekar, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Mumbai, agreed. “There is so much diversity in the type of colleges – some are rural, some urban, some semi-urban and some in tribal areas,” he said. Framing curricula that fit in all these disparate settings is a challenge and often means “dilution of the syllabus and a little compromise on quality”.

Suhas Pednekar, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Mumbai, agreed. “There is so much diversity in the type of colleges – some are rural, some urban, some semi-urban and some in tribal areas,” he said. Framing curricula that fit in all these disparate settings is a challenge and often means “dilution of the syllabus and a little compromise on quality”.

For the same reasons, any attempt at reform or innovation takes herculean effort and is hugely risky. The cost of mistakes is steep. “There are colleges which are good, then there are colleges which are not so good, so you have to keep all this in mind while introducing any new thing,” said Ramachandran. The authorities at Mumbai University know this all too well. Two years ago, its Vice-Chancellor had to relinquish his post because of a botched attempt at shifting to an on-screen system of evaluation. Tech glitches compounded by the shortage of permanent staff so delayed the process, the results were declared months late, affecting thousands.

Nevertheless, Mumbai and Osmania have both started and stuck to onscreen evaluation. Mumbai University will next introduce the credit-transfer system, said Pednekar.

Resource shortage

However, the problem of fund and faculty shortage is near-universal in these institutions. State-run institutions enrol over 85 percent of the student population but receive very meagre funds.

Most of the large affiliating universities are state-run and teachers have not been appointed to them for years. At some places, as many as 50 percent posts at the central level are vacant. Pune University, for example, has 495 sanctioned faculty positions out of which nearly 50 percent are vacant. Universities have devised their own mechanisms to address this shortage but that is also not enough.

The uneven quality is also owed to the fact that there is no uniformity in the way teachers are appointed. “In the unaided or self-financed departments [of colleges], there is more appointment of contractual teachers, who despite having same qualification and workload are paid less, which causes disparity and discontent,” Pednekar said. Mumbai University colleges have a very high proportion of self-financed courses, funded through student fees and not government support.

For CSJM University, with close to 1,000 affiliated colleges, conducting examinations and declaring results on time – more a logistical exercise than an academic one – is the biggest challenge. The University has over nine lakh students enrolled with it, with colleges spread across 14 districts of the state.

But with proper time management, and streamlined examination facilities and planning, it is able to fulfil both the objectives. There are 14 districts and examinations are conducted in around 550 centres each year. The university makes nodal centres in each district and coordinates with them for conducting exams. Last year, CCTV cameras were installed to deter cheating.

Vice-Chancellor Gupta pointed out that the “large number of students poses disciplinary problems as well” and with the large number of teaching and non-teaching staff, managing welfare programmes and keeping track of promotions are also difficult.

With administrative work claiming the bulk of the time and energy, research is neglected. “Universities are expected to create knowledge through research, which is not happening to a large extent,” admitted Pednekar. “The draft policy looks good on paper, but we will have to see how it is implemented.”

Letting go

The universities have already started letting go of their better-known institutions, allowing them to manage their exams internally. The higher education regulator, University Grants Commission, has encouraged colleges to apply for autonomous status. Recently, Mumbai University announced it will grant such status to eight more colleges taking the total to 36. University of Madras was the first to take such a step. In 1978, Madras Christian College, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda College and Loyola College in Chennai; and P.S. College of Technology in Coimbatore were granted autonomy. Vivekananda College was given partial autonomy for two postgraduate departments – chemistry and economics.

INTERVIEW: Adequate money has not been made available

Savitribai Phule Pune University, formerly University of Pune, has around 900 colleges, over 100 management institutions and another 100 research centres attached to it. Its degree courses and research centres enrol 7.5 lakh students each. Nitin Karmalkar, Vice-Chancellor, spoke to Careers360 about what it takes to run an institution of that size.

Q. How do you look at the recommendation of the draft NEP on downsizing big affiliating universities for their better functioning?

A. From 40,000 colleges and over 900 universities they intend to bring it down to 15,000 degree granting institutions. The largest structures are the state universities. They have their own issues – faculty recruitments have not happened for long, adequate money has not been made available. Earlier, institutions got funds under the Five-year Plan as well, which is not there. Now, all funding gets linked to their standing in National Institutional Ranking Framework or accreditation. We have been ranked among the best in the country but it is very challenging to maintain standards when there is depletion in faculty-numbers.

A. From 40,000 colleges and over 900 universities they intend to bring it down to 15,000 degree granting institutions. The largest structures are the state universities. They have their own issues – faculty recruitments have not happened for long, adequate money has not been made available. Earlier, institutions got funds under the Five-year Plan as well, which is not there. Now, all funding gets linked to their standing in National Institutional Ranking Framework or accreditation. We have been ranked among the best in the country but it is very challenging to maintain standards when there is depletion in faculty-numbers.

Plus, a new norm requires engineering institutions to be affiliated to technical universities and medical colleges to medical universities. This has brought inter-departmental research with medical colleges to standstill, lowering the university’s research output.

Q. What are the challenges you face as the Vice Chancellor of a large university?

A. Universities should be a place where research and teaching take place. But these are now examination conducting machines. Through the year, the departments are busy conducting exams, declaring results, awarding degrees. This affects the quality of education and research takes a back-seat. I am also facing challenges related to getting students placed.

Q. How are you addressing the problem of staff shortage?

A. We have 495 sanctioned faculty positions out of which nearly 50 percent are lying vacant. We have retained retired faculty-members, either as distinguished professors or as emeritus professors. They help in training the younger teachers. We have huge faculty shortage. The same problem is being faced by colleges. The fee structure is old and there has been no change in it for over a decade.

Q. Are you also facing a funds crunch?

A. We are facing major fund shortage. With the changing demands of society, we also need to come up with new courses, curriculum and centres and all this is to be done with our own corpus. That corpus is depleting as bank interest rates have gone down. Engineering colleges were a good source of income but with 50 percent of the seats going vacant, we have lost revenue there. The funding that we got from the centre has also reduced.

Q. How do you introduce reforms in a university with hundreds of affiliated colleges?

A. We are using technology in a big way. There is need for reform in the curriculum and the examination system also. Conducting examinations for 7.5 lakh students is a herculean task. You have to prepare the question paper, their delivery, their safety. Evaluation is another problem. People do not come for it because the remuneration is low. I personally believe it is our duty as teachers to evaluate papers and there should be no extra charge but we have an age-old system with no review of that payment structure.

Write to us at news@careers360.com.

Follow us for the latest education news on colleges and universities, admission, courses, exams, research, education policies, study abroad and more..

To get in touch, write to us at news@careers360.com.