Book Excerpt: Investigating the ‘mystery of the rabbit on the moon’

Team Careers360 | April 12, 2021 | 11:10 AM IST | 6 mins read

How Anil Bhardwaj, astrophysicist and director of Physical Research Laboratory, came to conduct experiments on Chandrayaan-1.

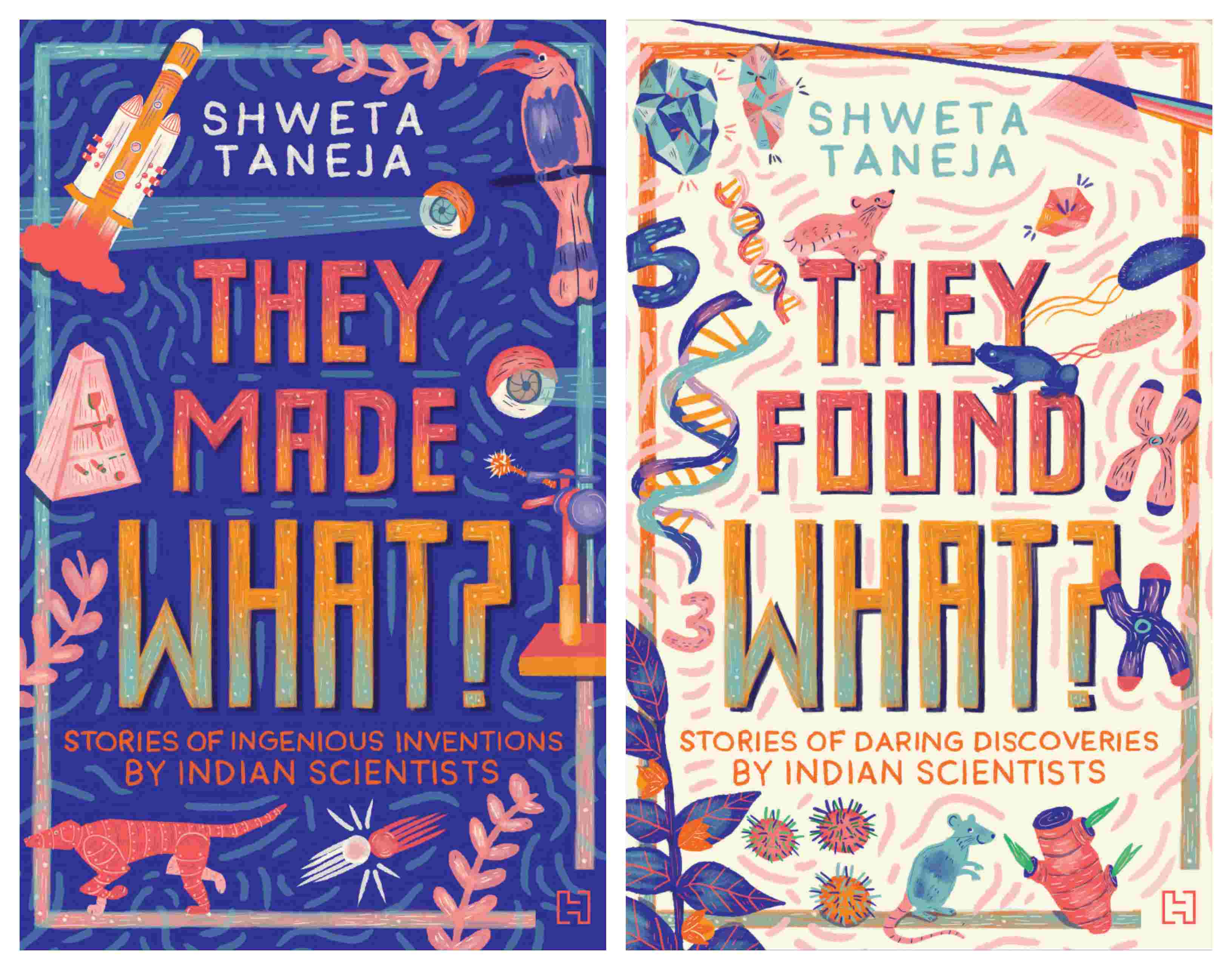

In the flip-book for kids, They Made What? They Found What? Shweta Taneja tells the stories of inventions and discoveries by some of India’s best-known scientists and also how they came to be who they are.

The year was 1975. It was a cool, summer evening in Lucknow. A sweaty eight-year-old Anil Bhardwaj trailed behind his older brother and his friends, dragging his cricket bat behind him. They had just won a cricket game against the other kids in the neighbourhood and were returning home, happy and spent.

The sun had set, and a full, bright moon hung low in the sky. Anil stopped to stare at the silvery globe. He noticed that a web of dark shapes swirled on its surface. With a little more staring, the shapes began to look like a round face with a snout, with two long ears popping out of it.

‘Look at the moon, Bhaiya!’ exclaimed Anil. ‘There’s a rabbit there!’

‘They’re just dark spots, Anil,’ his brother said, continuing his conversation with his friends.

Anil wasn’t convinced. What were those spots on the moon? he wondered. For the next few weeks, he decided to investigate the mystery of the rabbit on the moon. Every night, he would hurry out to the courtyard of his home to observe and track the moon. He jotted down how it changed its shape, size, colour and position in the sky in a notebook.

Soon, looking up at the night sky became a hobby. Anil began to add in the stars and the constellations that he could spot. His brother joined him in these astronomical adventures. They wrote down the positions of different planets – identifying them as bright objects in the sky that did not twinkle. The stargazers observed the movements of Venus, the positions of constellations as they popped up in different parts of the sky and the phases of the moon as it waxed and waned. Anil pored over the astronomy books in his school library and took the help of his science teacher to understand what he was observing.

Finally, he cracked the mystery! The dark spots on the moon – the ones that looked like a giant rabbit – were places on the lunar surface where ancient volcanoes had erupted billions of years ago.

Although the rabbit mystery was solved, Anil continued to be fascinated by the celestial body closest to Earth. It astonished him that although astronauts had landed on its surface, there was still so much that was unknown about Earth’s moon.

When he became a teenager, Anil was as bewitched by electronics as he was with all things lunar. Much to the dismay of his parents, he would wander around the house taking apart household appliances so he could look at their insides.

One day, his mother found that their steam iron had been tampered with. ‘Anil! What did you do?’ she cried out, knowing well that he was the culprit.

‘I wanted to know how it heats, steams and irons!’ he said, hiding the transistor component he was cradling in his hands.

By the time Anil enrolled in college, his interest in electronics had grown into a full-blown passion. At Lucknow University, while he was studying physics, maths and statistics, he even developed a small transistor, putting it together from scratch by soldering its components.

A big turning point came when Anil turned 18. A scientist from the USA came home for dinner with his parents. The visitor entertained the family with colourful stories of his adventures in science. That night, an inspired Anil resolved to become a scientist. ‘I want to research celestial bodies,’ he announced to his parents. And he went on to do just that.

The year 1986 was an extraordinary one for space lovers. Amateur astronomers across the world were getting ready for a rare celestial event: the Halley’s Comet was slated to make an appearance in the Earth’s neighbourhood. It was a once-in-a-lifetime event as the comet, which revolved around the sun, was visible from Earth only once every 75–76 years.

Anil and his friends went to a small observatory in Lucknow to witness the astronomical spectacle. The group held a night-long stakeout and were rewarded with the sight of the fiery comet, its long tail blazing across the sky.

‘What is it made of?’ Anil wondered. Within a few years, scientists had found the answer to his question. The glorious sight of the comet streaking across space was etched in his memory, and would go on to become a big part of his research in astrophysics.

Inspired by his encounter with the Halley’s Comet, Anil decided to study a curious phenomenon called ‘airglow’ at the Indian Institute of Technology, Banaras Hindu University (BHU), where he was pursuing a doctorate or a PhD in physics. His focus was on a little-known aspect called the ‘coma’, the hazy atmosphere surrounding a comet, which was made up of a cloud of gas, ice and dust. He also researched another fascinating occurrence – the aurora. Auroras are brilliant, multihued lights appearing across the sky in the polar regions of planets with magnetic fields, just like Earth. Auroras could happen on comets as well, and Anil studied them further.

Apart from a visit by the Halley’s Comet, the year 1986 saw other exciting developments in space science. For the first time ever, observational data from the faraway planet Uranus was beamed back to Earth by Voyager 2. In 1977, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) launched Voyager 2, a fly-by* space probe to study the outer planets – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. It had taken 12 years for Voyager 2 to reach Neptune! This was due to a rare alignment of the outer planets. Otherwise it would have taken Voyager 2 almost three times the 12 years it took to reach Neptune.

As data from Uranus reached NASA by 1986, Anil was one of the few Indian scientists to study it. It took him a year to analyse this data, as in the 1980s, the technology to analyse massive datasets was limited. He didn’t have a personal computer or a laptop. So he would head to the computer centre at his institute every morning, where he would give the operator punched cards with typed codes written on them. The operator would run the codes on the computer, and Anil would return to the lab in the evening to look at them.

Phew! It was hard work, but well worth the trouble to discover the secrets of Uranus. Along with other scientists, Anil’s research uncovered the presence of a layer of bright light in Uranus’s atmosphere, a phenomenon which was named ‘electroglow’.

Having completed his doctoral research on auroras, outer planets, comets and faraway celestial bodies, Anil landed his first job as a scientist at the Space Physics Laboratory at the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC), in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala.

The state-of-the-art laboratory explored how physics worked in different planetary atmospheres. He continued studying comets and outer planets at VSSC, and soon became a leading expert on space and planetary sciences in India.

Cut to the early 2000s. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), the country’s premier space agency, was planning to expand India’s planetary exploration program. In 2003, a group of leading space scientists from around the country met in Bengaluru and decided to launch India’s first moon mission. Anil was one of the scientists present at this historic meeting. This was the opportunity that he had been waiting for! He could finally build his own experiment – called a ‘payload’ – and send it to the moon to collect the kind of data he had dreamed of as a child.

*A fly-by probe is a robotic spacecraft that does not go into orbit around a planet but flies past it.

Write to us at news@careers360.com.

Follow us for the latest education news on colleges and universities, admission, courses, exams, research, education policies, study abroad and more..

To get in touch, write to us at news@careers360.com.