CLAT 2025: Domicile quotas in NLU admissions spark diversity, merit debate

Musab Qazi | December 1, 2024 | 01:05 PM IST | 9 mins read

NLSIU Bangalore’s land deal fetched CLAT 2025 aspirants 10 more seats in a premier law school. Domicile quotas in RGNUL, MNLU, GNLU, NALSAR and others, their varying criteria, remain a fractious issue.

CLAT 2026 College Predictor

Know your admission chances in National Law Universities based on your home state & exam result for All India Category & State Category seats.

Try Now

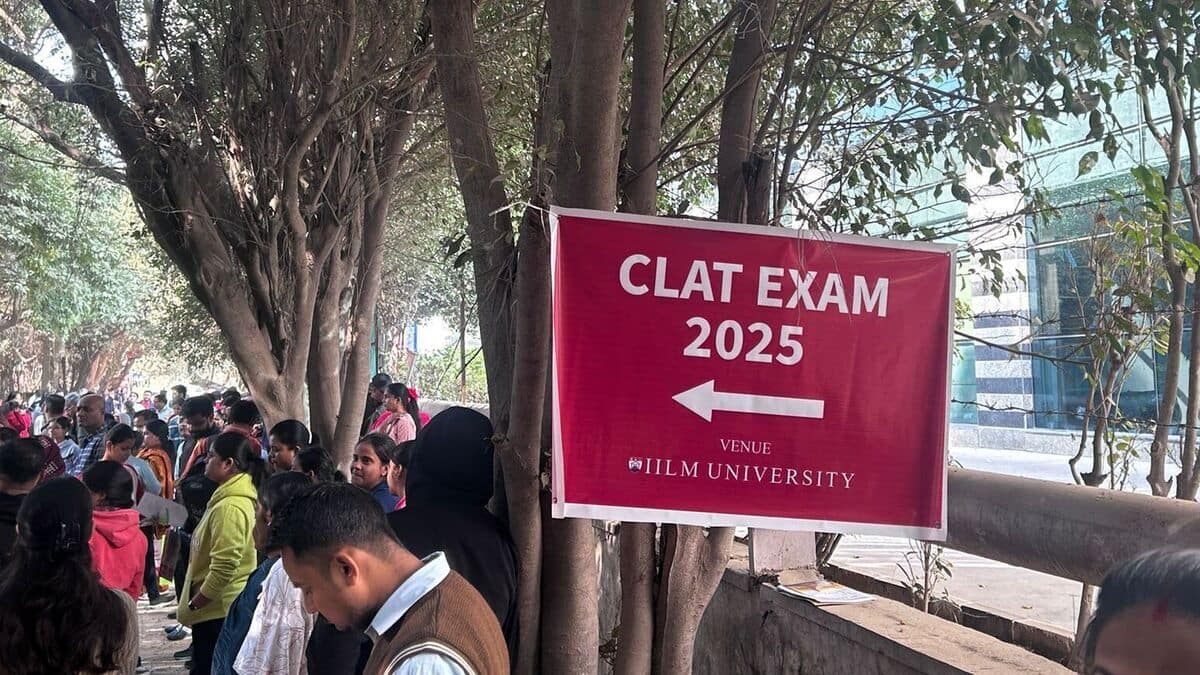

NEW DELHI: Aspirants writing the Common Law Entrance Test (CLAT 2025) on December 1 suddenly had the seats open to them at the National Law School of Indian University (NLSIU) Bangalore, increased last month. The oldest 'national' law school in the country agreed to add 10 supernumerary seats in its undergraduate programme for students hailing from Karnataka.

Latest: CLAT 2026 Result Out; Direct Link

New: CLAT 2026 Final Answer Key Out - Download PDF

CLAT 2026 Tools: College Predictor | Rank Predictor

CLAT 2026: Opening and Closing Ranks | Expected Cutoff | Marks vs Rank

The move was in exchange for seven acres of land being given to the institute by the Bangalore University. These seats will be in addition to the 25% of seats already reserved for local candidates at NLSIU Bangalore since 2021.

The openly transactional move, which followed negotiations between the state and university authorities as well as the now-retired Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud, has further cemented Karnataka and even other state governments' position in the matters of seat distribution at their respective National Law Universities (NLUs) and consolidated domicile quotas at these institutes, despite long-standing opposition from students, alumni and the management.

Established all around the nation over the last four decades, the 27 NLUs are deemed as exemplar institutes dedicated to improving the standard of legal education in the country. Indeed, many of them, especially the older ones, continue to feature at the top of ranking tables and are among the most sought-after study destinations for budding lawyers and legal scholars.

The NLUs are viewed to be in the same league as other institutes of national importance, especially the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) and the Indian Institutes of Management (IIM). Also like them, they hold a national entrance test, the Common Law Admission Test (CLAT exam) for admissions and coordinate amongst themselves through the Consortium of NLUs.

Yet, there's a key difference in the way NLUs are set up and run. Unlike IITs and IIMs, which are established by national laws and are funded by the central government, the law universities are essentially state institutions, albeit with a 'national character'.

All the NLUs have come into being through statutes enacted by the state legislatures, with land and initial funding provided by the state governments. Many of them continue to receive relatively small but regular aid from their respective states.

RGNUL, MNLUs, NALSAR: Domicile quota

This dependence has allowed the state governments to compel NLUs to set aside a portion of their seats for their domicile candidates. Amid student protests and court battles, most of the varieties have come to have local reservations, with their quantum varying anywhere between 10% (Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law [RGNUL] Patiala,) and 72% (Maharashtra National Law Universities [MNLUs]).

In the past few years, the local quotas have only grown in size. In 2021, the National Academy of Legal Studies and Research (NALSAR), Hyderabad, expanded domicile reservation from 20% to 25%. With Maharashtra recently introducing a 10% Socially and Economically Backward Class (SEBC) quota for Marathas, MNLU Mumbai and Aurangad have set aside almost three-fourths of their intake for local candidates. The states which got newer NLUs made it a point to institute a state quota right from the inception.

The proponents of domicile quotas, mainly state public representatives and lawyers' associations, believe that locals should have the first right over law schools as it's the state resources crucial for functioning of these institutes.

The opponents, which include present and past heads of NLUs and student bodies, argue that such quotas dilute the national character of law schools and limit students' exposure to learners from different parts of the country. Some have even asked for 'nationalising' these institutes by bringing them under the ambit of a parliament legislation.

NLU Delhi, NALSAR Hyderabad: Differing opinions

While the opinion on the subject remains divided on NLU campuses, it no longer elicits such strong reactions as were witnessed a few years ago.

Most of the students appear to have accepted that the provincial quota is here to stay, even as they hope that its proportion is kept limited. And despite almost all the states having their own NLUs – some northeastern states and Jammu and Kashmir, now a union territory, are the exceptions – the stakes are particularly higher at the older, more popular ones, NLSIU Bengaluru, NALSAR Hyderabad, and WBNUJS Kolkata.

Some like Ranbir Singh, who helmed NALSAR and NLU Delhi for a decade each as the founding vice chancellor (VC), vehemently believe that local reservations have been a major barrier in NLUs achieving their stated objective of being model institutes of legal education.

He cites the absence of any domicile reservation at NLU Delhi – the institute had introduced 50% local quota at the instance of Delhi government but it was struck down by the Delhi High Court (HC) as the major factor for the institute constantly occupying the second position in the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) for law, despite being relatively new in the NLU network.

"Leave some institutes at least (without state quotas). The reservation policy is not very healthy for centres of excellence. It certainly (impacts quality of education)," he said. NLU Delhi holds its own entrance test, the AILET exam, and is not a member of the CLAT consortium.

While conceding that the domicile quota does help certain states with large tribal populations, he added, "Reservation certainly brings a local flavour, but I have no hesitation in saying that the concept has turned into creating glorified law colleges”.

Singh said the quotas lead to the “language problem” at premier institutes. "As the medium of instruction in NLUs is English, some students struggle with the language. We maintain a high quality in research and education. But if your base is poor, it causes mental health problems," he said.

However, Faizan Mustafa, who headed NALSAR Hyderabad and NLU Odisha before being appointed VC at Chanakya NLU, Patna, offers a counter-take. "Domicile quota has not lowered standards as people with very high merit are admitted. It is the general category. The percentage of quota differs from NLU to NLU. Some have 50% as well. Generally, candidates from metropolitan cities of particular states benefit from it," he said.

Divide between NLU students: Local vs non-local

According to NLU students, the most noticeable impact of domicile reservation policies, on certain campuses, has been a sharp divide between local and non-local students, coupled with the assertion of regional and linguistic identities.

"When there's a quota, a significant number of students from a state come to the university and, being locals, they already hold some power. For example, NALSAR has a distinct Telugu-speaking group. It's easy for them to do politics on regional and linguistic identity because there's a sizeable population. They tend to get isolated from others while being more attached to their own," said Hamza Khan, a NALSAR student, who hails from Uttar Pradesh.

The cleavage between the two student groups can have other consequences beyond socialising and campus politics. Speaking on the condition of anonymity, an MNLU Mumbai student, who, though Maharashtra domiciled, was admitted through All India Quota, said,

"As a concept, [domicile reservation] is really good, but I think it's not working practically and tangibly. My friends from other parts of the country feel a bit underrepresented considering there's 60-70% reservation for state students. The social barriers make integration difficult. Even in the classroom, they are a bit shy and tend to keep to themselves. It also affects their participation in varsity activities," he said.

The local students' dominance sometimes also fuels the perception of discrimination and causes resentment among non-locals. A Telangana student enrolled at Tamil Nadu National Law University (TNNLU) narrated two incidents, one about him being allegedly facing tougher scrutiny in a moot court competition and another about his friend being allegedly overlooked for the position of the captain of the varsity basketball team, to underscore the bias ostensibly prevalent on campus. Careers360 couldn't independently verify these claims.

To be sure, most of the NLU students who spoke with Careers360 didn't report any prejudicial treatment.

Khan opines that as long as the administrative staff and faculty hirings aren't bound by local reservations, the universities will continue to have a harmonious and equitable atmosphere. "It's only when the administration is also dominated by a certain region, it results in an unhealthy nexus," he said.

MNLU, GNLU: Quota inconsistency

What makes the issue more complex is the inconsistency in how domicile reservation is applied at different NLUs. While some institutes have compartmentalised horizontal local quotas, where existing caste-based and other reservations are proportionally applied on the state as well as all-India seats, some like Gujarat National Law University (GNLU) have non-compartmentalised reservations for state students.

In contrast, Maharashtra NLUs' domicile seats are meant only for students belonging to various disadvantaged groups, while all national seats are unreserved. While this arrangement is possibly aimed at ensuring adequate representation to the variety of marginalised groups in the state, it further adds caste and class divide to the regional split in the student body.

Also read CLAT Cut-off 2025: Category-wise cut-offs for LLB admission at NLUs

Satej Desale, a GNLU student from Maharashtra, who belongs to the Other Backward Class (OBC) category, highlights some of the consequences of these inconsistencies. "I couldn't get into West Bengal National University of Juridical Sciences (NUJS Kolkata) because its OBC quota is only applicable for those from West Bengal. In GNLU, most of the local students belong to the general category. They all hail from large cities like Ahmedabad and Vadodara, with no representation from mofussil towns of the state," he said.

Nilabja Majumdar, a student at WBNUJS Kolkata, contrastingly found local reservations improving the diversity at the institute. "I have been seeing a steady rise in the number of students from across West Bengal, including districts such as Darjeeling, Howrah, North 24 Parganas and South 24 Parganas. It's really leading to social inclusion," he said.

‘IIT-isation’ of NLUs: Need for uniformity

Desale wants more uniformity in seat distribution across NLUs, with domicile quota being restricted to 20% or less, even as he opposes their 'IIT-isation'. "There should be some uniformity, if not a complete one, at least in reservation. If a state is funding the university, its people should get primacy. One of the objectives of creating NLUs was accessibility of studying law," he said.

Also read CLAT 2025 and beyond: What’s new in degree, diploma, certificate law courses

The MNLU student, on the other hand, said that instead of tinkering with quota percentages, the focus should be on better assimilating students from different backgrounds. "The reservation requirements differ from state to state due to population and other factors," he said.

Faizan Mustafa, however, advocates a complete overhaul of NLU's governing and funding system to address these issues. "Ideally, NLUs should follow central reservation policy and the centre should entirely fund these institutions. National institutions should not become provincial. They cannot be increasing their fees all the time to raise requisite funds as every fee hike has an effect on diversity and underprivileged students find it difficult to study in these institutions," he said.

Follow us for the latest education news on colleges and universities, admission, courses, exams, research, education policies, study abroad and more..

To get in touch, write to us at news@careers360.com.

Next Story

]DU Law Faculty stays with CLAT 2025 for 5-year LLB admissions but plans separate exam for the future

Delhi University’s Faculty of Law offers BBA LLB and BA LLB courses; admission in 2025 is through the CLAT exam. The dean spoke of the demand for separate tests, new courses, Manusmriti in LLB syllabus and plans for Campus Law Centre.

Shradha Chettri